Front cover

Amnesty International Publications | 2013

| 1. |

Introduction and Summary……………………………………………………………..

|

5

|

| 2. |

Legal framework …………………………………………………………………………

|

7

|

|

2.1

|

International legal obligations …………………………………………………….

|

7

|

|

2.2

|

The Constitution ……………………………………………………………………..

|

8

|

|

2.3

|

A range of repressive laws and decrees………………………………………..

|

9

|

| 3. |

Human rights violations against peaceful activists ………………………………..

|

11

|

|

3.1

|

Arrest and pre-trial detention …………………………………………………….

|

11

|

|

3.2

|

Unfair trials……………………………………………………………………………

|

12

|

|

3.3

|

Prison conditions ……………………………………………………………………

|

12

|

|

3.4

|

House arrest and other post-imprisonment penalties………………………..

|

12

|

| 4. |

Illustrative cases of prisoners of conscience ………………………………………

|

14

|

|

4.1

|

Bloggers ………………………………………………………………………………

|

14

|

|

4.2

|

Catholic Social Activists and Bloggers ………………………………………….

|

16

|

|

4.3

|

Human Rights and Social Justice Activists ……………………………………..

|

18

|

|

4.4

|

Labour Rights Activists……………………………………………………………..

|

19

|

|

4.5

|

Land Rights Activists ……………………………………………………………….

|

20

|

|

4.6

|

Political Activists …………………………………………………………………….

|

21

|

|

4.7

|

Religious followers ………………………………………………………………….

|

25

|

| 5. |

Conclusion and Recommendations……………………………………………………

|

28

|

| Appendix 1: |

Articles of the 1999 Penal Code used to imprison activists and others

|

31

|

| Appendix 2: |

Comments and recommendations on Viet Nam’s draft revised constitution

|

33

|

| Appendix 3: |

List of prisoners of conscience named in this report

|

36

|

|

|

|

|

|

1. INTRODUCTION AND SUMMARY

“A person is independent only if he has his freedom. And only when his rights are respected and fully protected by the laws then he is truly free.”- Tran Huynh Huy Duc, 47, a prisoner of conscience serving a 16-year jail sentence since May 2009.

Like Tran Huynh Huy Duc, human rights defenders and other activists in Viet Nam are typically at risk of arbitrary arrest and lengthy detention for speaking out or thinking differently. Over the years, hundreds have been arrested, charged, detained or imprisoned through the use of restrictive laws, or spurious charges.1 They include peaceful bloggers, labour rights and land rights activists, political activists, religious followers including Catholic activists and Hoa Hao Buddhists, human rights and social justice advocates, and even songwriters.

As a party to the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), Viet Nam has the duty to respect and protect the right to free speech. Yet, at least 75 people are currently jailed for nothing more than the peaceful exercise of their right to freedom of expression.

Amnesty International considers them all prisoners of conscience, and calls for their immediate and unconditional release.

Prisoners of conscience in Viet Nam face arbitrary pre-trial detention for several months, are held incommunicado without access to family and lawyers, and are subsequently sentenced after unfair trials to prison terms ranging from two to 20 years or even, in some cases, life imprisonment. Many are held in harsh conditions amounting to cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment, with some of them subjected to torture and other ill-treatment, such as beatings by security officials or other prisoners.

This situation derives from restrictions in law and practice to the right to freedom of expression, and shows that Viet Nam is in violation of its international legal obligations to respect, among other rights, the right to freedom of expression, the right to a fair trial and the right not to be subjected to torture, cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment. Amnesty International is particularly concerned about vaguely worded language in laws and decrees which has been repeatedly used over the years to restrict free speech and lock people up. These laws need to be urgently revised as they are not in line with international human rights standards.

In this report, Amnesty International provides a brief overview of Viet Nam’s legal framework and international obligations. The report then highlights the range of human rights violations that human rights defenders and other activists are subjected to in Viet Nam when they become prisoners of conscience. Lastly, it provides detailed information on 75 individuals currently in jail after being tried and convicted for the peaceful exercise of their right to freedom of expression. This list is illustrative and by no means exhaustive. There are numerous others behind bars who may also be prisoners of conscience in Viet Nam,2 and others who are currently in pre-trial detention.3 Additionally, many are under house arrest and/or subject to brief arrest and detention.4

What is a prisoner of conscience?

A prisoner of conscience is a person imprisoned or otherwise physically restricted because of their political, religious or other conscientiously-held beliefs, ethnic origin, sex, colour, language, national or social origin, economic status, birth, sexual orientation or other status who has not used violence or advocated violence or hatred. Amnesty International considers people imprisoned solely for peacefully exercising their right to freedom of expression to be prisoners of conscience, and calls for their immediate and unconditional release everywhere in the world.

Key recommendations

At a time when the Viet Nam government seeks election to a seat on the UN Human Rights Council for 2014-2016, the authorities should ensure that the right to freedom of expression is respected and upheld in their country. In particular, Amnesty International recommends that the Viet Nam authorities undertake the following steps to ensure that human rights defenders and other activists are able to freely express their opinions and beliefs:

Release immediately and unconditionally all prisoners of conscience, whether they are in pre-trial detention, imprisoned after conviction by a court, or under house arrest, and ensure that all those released are able to effectively access their right to remedy in accordance with international law, and that they are provided with reparations for their suffering;

Take measures to ensure that human rights defenders, peaceful activists and religious followers are free from violence, discrimination and the threat of criminalisation;

Repeal or else amend provisions in the 1999 Penal Code to ensure that ambiguous provisions relating to national security are clearly defined or removed, so they cannot be applied in an arbitrary manner to stifle legitimate and peaceful dissent; and

Ensure that the new constitution recognises the rights provided for in Articles 19, 21, and 22 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights in terms fully consistent with those articles and that do not circumvent Viet Nam’s international human rights obligations as a state party.

2. LEGAL FRAMEWORK

The rights to freedom of expression, as well as the right not to be subjected to arbitrary detention or to torture or other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment, and the right to a fair trial are protected under international law. In particular, they are protected under treaties which Viet Nam has ratified, such as the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR). 5 The Viet Nam Constitution affirms these rights, but also provides for limitations on them beyond what is permitted under international law. There are also numerous laws and decrees which prescribe or permit restrictions on freedom of expression and other human rights, in violation of Viet Nam’s obligations under international law. Amnesty International has long made recommendations to Viet Nam’s government on the need to ensure that laws relating to freedom of expression are brought into line with international human rights law and standards.6 The Universal Periodic Review Working Group also made several recommendations relating to freedom of expression and adherence to the ICCPR, when Viet Nam came under review in May 2009.7

2.1 INTERNATIONAL LEGAL OBLIGATIONS

As a state party to the ICCPR and a number of other international human rights treaties, Viet Nam is bound under international law to respect, protect and fulfil the rights set out in those treaties. The obligation to respect means that state officials must not interfere with or curtail individuals’ exercise of their human rights. Viet Nam is also obliged to exercise due diligence to protect individuals and groups against human rights abuses by others, including by other individuals. It must also fulfil human rights by taking positive action to facilitate the exercise of those rights by people within its jurisdiction.

In particular, and of particular relevance with regard to prisoners of conscience, Viet Nam is obliged under international law to respect the right to freedom of expression, as set out in Article 19 of the ICCPR:

“Everyone shall have the right to freedom of expression; this right shall include freedom to seek, receive and impart information and ideas of all kinds, regardless of frontiers, either orally, in writing or in print, in the form of art, or through any other media of his choice.”

Any restrictions on the exercise of this right must meet all elements of a three-part test: it must be provided by law; only for certain specified permissible purposes (respect for the rights or reputations of others, or protection of national security, public order, or public health or morals); and it must be demonstrably necessary in the circumstances for one of those specified purposes. The Human Rights Committee, the body of independent experts established under the ICCPR for monitoring its implementation by states, has underlined that the test of necessity means that any restrictions, whether set out in law or as applied by the administrative or judicial authorities, must be the least intrusive means to achieve the legitimate purpose and must be proportionate to the interest to be protected.8 Moreover, when a state party imposes restrictions on the exercise of freedom of expression, these may not put in jeopardy the right itself.9

As a state party to the ICCPR, Viet Nam is also obliged to respect the rights to freedom of peaceful assembly and of association, where similar limitations apply with regard to any restrictions which may be imposed on the exercise of these rights, and freedom of thought, conscience and religion or belief.

Under the ICCPR, Viet Nam is also obliged to respect rights around arrest and fair trial. This includes: (1) the right not to be arbitrarily arrested or detained; the right of anyone who is arrested to be promptly informed of charges against them, to be brought before a judge, and to be able to challenge their detention before a court; and the right to trial within a reasonable time or else to be released if the detention is not lawful (Article 9); (2) the right to a fair trial by a competent, independent and impartial court, including the right to legal counsel before trial and the right to adequate time and facilities to prepare a defence and the right not to be compelled to testify or confess guilt (Article 14); and (3) the right to be treated humanely (Article 10), including being allowed access to the outside world, and to be free from torture or other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment (Article 7).

Many of these and other obligations of states are reflected also in other international standards, such as, in particular, the UN Body of Principles for the Protection of All Persons under Any Form of Detention or Imprisonment (the UN Body of Principles), adopted by consensus by the UN General Assembly in 198810 and the UN Standard Minimum Rules for the Treatment of Prisoners (Standard Minimum Rules).

States are also under an obligation to ensure that anyone whose human rights are violated has the right to an effective remedy for those violations (ICCPR, Article 2).

2.2 THE CONSTITUTION

The 1992 Viet Nam Constitution affirms the rights to freedom of expression, association and peaceful assembly under Article 69, but only “in accordance with the provisions of the law”. Similarly, the draft new constitution, which has been under consultation this year11 provides under Article 26:

“Citizens are entitled to freedom of speech and freedom of the press; they have the right to receive information and the right of assembly, association and demonstration in accordance with the law.” 12

Although the draft revised constitution generally protects the rights to freedom of expression, association and peaceful assembly, it also subjects these rights to limits that might be imposed by national legislation. These limits as set out by the current and draft constitution are currently too vague and broad and go beyond the extent of restrictions which may be permitted under the ICCPR.13

The current constitution does not adequately protect the right to a fair trial as required under Article 14 of the ICCPR. Also, while Article 71 of the current constitution14 already prohibits torture, Viet Nam has yet to provide in law a clear definition of what acts constitute torture.

The draft revised constitution also prohibits torture in Article 22.2,15 and in Article 32 sets out a limited guarantee of fair trial rights and reparations for breaches of those rights (for further comments on the draft revised constitution, see Appendix 2).16

Amnesty International recommends that a full definition of torture be incorporated into Viet Nam law, with adequate penalties for this crime, in line with the provision in Article 1 of the UN Convention Against Torture, and other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (UNCAT).

Viet Nam is a signatory to UNCAT and is set to ratify it in 2014. As a signatory to the Convention, Viet Nam is expected to act according to the spirit of its provisions and has the obligation to refrain from any actions that may defeat the object and purpose of the Treaty prior to its entry into force.

2.3 A RANGE OF REPRESSIVE LAWS AND DECREES

The case of Dinh Dang Dinh

Dinh Dang Dinh, 50, is a former soldier and chemistry teacher living in Kien Duc, Dak R’Lap district, Dak Nong province in the Central Highlands, who became an environmental activist and blogger. He had initiated a petition against bauxite mining in the Central Highlands. He was arrested in December 2011 and sentenced by Dak Nong People’s Court to six years’ imprisonment in August 2012 under Article 88 of Viet Nam’s Penal Code for “conducting propaganda” against the state. He was accused of writing and posting anti-government documents on the internet and calling for democracy and pluralism. His trial lasted just three hours and the appeal hearing, at which his sentence was upheld, only 45 minutes. On leaving the appeal court, he was manhandled into a truck and beaten over the head with clubs by security officials.

Numerous laws and decrees circumscribe and restrict the right to freedom of expression in Viet Nam, including, among others: Internet decrees; the Press Law (amended in 1999) and the January 2011 Decree No 01/2011 on administrative sanctions in the press and publication field; the Publishing Law; the State Secrets Protection Ordinance; and above-all the 1999 Penal Code. Ambiguous and loosely-worded provisions contained in these laws are used to stifle the right to freedom of expression and related rights, and breach Viet Nam’s international human rights obligations under the ICCPR.17

Of particular relevance to political activists and human rights defenders such as Dinh Dang Dinh (see case above), the authorities typically use vaguely worded provisions of the national security section of the 1999 Penal Code, with penalties of imprisonment for from two to 20 years or life imprisonment as well as the death penalty. Specifically, Article 79 (Carrying out activities aimed at overthrowing the people’s administration) and Article 88 (Conducting propaganda against the Socialist Republic of Viet Nam) are used to punish peaceful dissenting opinions and actions. Article 87 (Undermining the unity policy) is most often used against members of religious and ethnic groups. Article 89 (Disrupting security) has been used against labour activists. Article 258 (Abusing democratic freedoms to infringe upon the interests of the State, the legitimate rights and interests of organizations and/or citizens), which comes under the chapter on “Crimes infringing upon administrative management order” of the Penal Code, is also used to criminalise the exercise of freedom of expression. This provides for up to seven years’ imprisonment. The full text of these articles can be found at Appendix 1.

In 2011, the UN Working Group on Arbitrary Detention has stated in its Opinions on individual cases that Viet Nam’s “broad criminal law provisions” are “inherently inconsistent” with the rights guaranteed by the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and the ICCPR.18 It is also worth noting that individuals in Viet Nam have been protesting against these vaguely worded provisions within the Penal Code. For example, in July 2013, a group of young bloggers in Viet Nam began a campaign calling for a review of Article 258 of the Penal Code. A petition entitled “Declaration 258” was signed by around 100 bloggers and presented in August 2013 to human rights organizations, UN agencies and diplomatic representations in a request for support.19

While there are various laws and decrees restricting the use of the Internet, these are not known to have been directly used to punish dissidents. However, on 1 September 2013, Decree No 72 on Management, Provision and Use of Internet Services and Online Information came into effect. This decree has been widely criticized for prohibiting the sharing of news reports on blogs and social media, and for the prohibition on “Opposing the Socialist Republic of Vietnam; threatening the national security, social order and safety; sabotaging the national fraternity…” which is the same vaguely worded language used to criminalize peaceful dissent in provisions of the Penal Code. Amnesty International calls for the repeal, or else amendment of this law to ensure that its provisions are fully consistent with international human rights law and standards.

3. HUMAN RIGHTS VIOLATIONS AGAINST PEACEFUL ACTIVISTS

Amnesty International considers those imprisoned solely for peacefully exercising their right to freedom of expression to be prisoners of conscience who should be immediately and unconditionally released.20 The jailing of such individuals clearly violates their right to freedom of expression. In addition, many are subjected to other human rights violations such as arbitrary arrest and detention; denial of a fair trial; and torture or cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment.

3.1 ARREST AND PRE-TRIAL DETENTION

After arrest, human rights defenders and other activists are often held in incommunicado detention for lengthy periods of time, in some cases up to 18 months. Family members are not allowed to visit and are not provided with information about their relative. For example, blogger Nguyen Van Hai, known as Dieu Cay, was held for investigation in incommunicado detention for almost two years, from October 2010 until his trial in September 2012. During much of that time, his family did not know where he was detained.

Article 9(3) of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) to which Viet Nam is a state party stipulates that anyone held on a criminal charge is entitled to trial within a reasonable time or to release pending trial. Further, Viet Nam’s Code of Criminal Procedure sets a maximum period of pre-trial detention of 16 months for those charged with “especially serious crimes”, that is those in the national security section of the Penal Code. It is worth noting that the period of almost two years for which Nguyen Van Hai was held in pre-trial detention contravened Viet Nam’s national legislation.

Amnesty International is also concerned about the use of incommunicado detention against human rights defenders and other peaceful activists. The UN Body of Principles provides explicitly that detainees have the right to have their family or friends informed of their detention, and to be able to communicate with family and legal counsel. These rights are also fundamental safeguards against other human rights violations including torture and other ill-treatment. Incommunicado detention – detention without access to the outside world – facilitates torture and other ill-treatment. Depending on the circumstances,21 it can itself constitute torture or other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment. Prolonged incommunicado detention is inconsistent with the right of all detainees to be treated with respect for human dignity and the obligation to prohibit torture or other ill-treatment or punishment.

Most of those in pre-trial detention do not have access to a lawyer until shortly before their trial, and so have no time to prepare an adequate defence, in violation of Viet Nam’s obligation under article 14 of the ICCPR.

3.2 UNFAIR TRIALS

Viet Nam’s judiciary is not independent from the government. Trials of dissidents are routinely unfair, falling far short of international standards of fairness. Despite some provisions providing for a right to a fair trial in Viet Nam’s 2003 Criminal Procedure Code, there is no presumption of innocence in practice, no opportunity for suspects and defendants to call and examine witnesses, and often a lack of access to competent and effective defence counsel. Judgements appear to be decided beforehand, and trials often last for only a few hours. For example, in the trial of Tran Huynh Duy Thuc, Nguyen Tien Trung, Le Cong Dinh and Le Thanh Long on 20 January 2010, the judges deliberated for only 15 minutes before returning with the full judgment. It took 45 minutes for judges to read the judgment, strongly suggesting that it had been prepared in advance of the hearing.

Amnesty International has also received information about police harassment and sometimes short-term arrest of family members and supporters of dissidents, who were attempting to observe trial proceedings. These practices are incompatible with Viet Nam’s obligation under international law to respect and ensure the right to a fair and public trial before a competent, independent and impartial court, including the right to legal counsel before trial, the right to adequate time and facilities to prepare a defence, and the right to call and examine witnesses.

3.3 PRISON CONDITIONS

Prison conditions in Viet Nam are harsh, with inadequately nutritious food and inadequate health care that fall short of the minimum requirements set out in the UN Standard Minimum Rules and other international standards. Prisoners of conscience have been held in solitary confinement as a punishment or in isolation for lengthy periods. As underlined by the UN Human Rights Committee,22 which monitors compliance with the ICCPR, and the UN Special Rapporteur on torture23 prolonged solitary confinement – particularly where combined with isolation from the outside world – may amount to torture or other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment.

Prisoners of conscience have also been subjected to ill-treatment, including beatings by other prisoners with no intervention by prison guards. Viet Nam’s obligation under international law to ensure the right of all persons within its jurisdiction not to be subjected to torture and other ill-treatment means that not only must state officials not commit acts of torture or other ill-treatment, but that Viet Nam must take effective steps to prevent such abuses by private persons. It has a heightened responsibility to ensure the rights of people within state custody are respected, and in this regard has an obligation under international law to exercise due diligence to protect people in detention from inter-prisoner violence.

Some prisoners of conscience are frequently moved from one detention facility to another, often without their families being informed. Monthly visits by family members are permitted, but are sometimes arbitrarily denied without reason. All visits are conducted in the presence of guards who frequently intervene to prevent discussion of perceived sensitive topics.

3.4 HOUSE ARREST AND OTHER POST-IMPRISONMENT PENALTIES

Individuals imprisoned for the peaceful expression of their views and beliefs are commonly sentenced to periods of house arrest or probation on release ranging from three to five years.

As such they continue to be prisoners of conscience while under such restrictions, unable to exercise their right to freedom of movement. They are subjected to regular questioning, surveillance, restrictions on movement and harassment by local police. Moreover, article 92 of the Penal Code specifies that all those convicted for crimes in the national security section shall “be deprived of a number of civic rights for between one year and five years, subject to probation, residence ban for between one year and five years, confiscation of part or whole of the property.”

Under international law, it is not permissible to impose any punishment for the peaceful exercise of the right to freedom of expression. Those detained solely for the peaceful exercise of their right to freedom of expression are prisoners of conscience who should be released immediately and unconditionally, without any subsequent, additional or alternative penalties or measures such as surveillance, harassment, house arrest or other restrictions on their right to freedom of movement, or confiscation of their property. Any such penalties or measures imposed on such individuals are violations of their right to freedom of expression.

4. ILLUSTRATIVE CASES OF PRISONERS OF CONSCIENCE

The following non-exhaustive list of prisoners of conscience in Viet Nam is divided into general categories related to activities and reasons for imprisonment, including bloggers, labour rights activists, land rights activists, political activists, religious followers, Catholic social activists and bloggers, human rights and social justice activists. Please note, however, that in many cases there is overlap and individuals will fit into more than one category. For an alphabetical list of the 75 prisoners of conscience included here, see Appendix 3.

4.1 BLOGGERS

- FREE JOURNALISTS’ CLUB OF VIET NAM

Well-known and popular bloggers Nguyen Van Hai, known as Dieu Cay (“peasants pipe”), “Justice and Truth” blogger Ta Phong Tan, and Phan Thanh Hai, known as AnhBaSaiGon, were tried in September 2012 under Article 88 of the Penal Code for “conducting propaganda” against the state. They are the founding members of the independent Free Journalists’ Club of Viet Nam, established in September 2007 to promote freedom of expression as an alternative to state-controlled media. Ho Chi Minh City People’s Court sentenced them to 12, 10 and four years’ imprisonment respectively, with three to five years’ house arrest on release. The trial lasted only a few hours and failed to meet international fair trial standards. Further, their families were harassed and detained to prevent them from attending the trial. Only three witnesses out of nine summoned were present and the defendant lawyers’ speeches were cut short so they were not able to provide a proper defence. Their trial was postponed three times before it was held on 24 September 2012, by which time the bloggers had been held in pre-trial detention for between one and almost two years.

The three bloggers wrote on a variety of issues, including social injustice, human rights concerns and national sovereignty. They also participated in peaceful gatherings in 2007 to protest about China’s policies towards Viet Nam, which they regarded as infringing national territorial integrity. This is a controversial subject about which many Vietnamese people feel strongly.

Nguyen Van Hai (m), 61, was first arrested in April 2008 on politically-motivated charges of tax evasion and sentenced to two-and-a-half years’ in prison. Instead of being released at the end of his sentence in October 2010, he was held for further investigation. During this extended detention period, his family and lawyer were frequently refused permission to visit him and questions about his health condition – reportedly poor – were not answered. During the trial, Nguyen Van Hai reportedly stated that he had never acted against the state but was only “frustrated by injustice, corruption and dictatorship, which does not represent the state but some individuals.” He also insisted on the right to freedom of expression in accordance with international treaties to which Viet Nam is party. His 12-year prison sentence was upheld on appeal on 28 December 2012. In June 2013, he went on hunger strike in protest at the harsh treatment of himself and other political prisoners at Prison No 6 in Nghe An province. He ended the hunger strike after 38 days when he was informed by an official that his complaint would be investigated.

Nguyen Van Hai (m), 61, was first arrested in April 2008 on politically-motivated charges of tax evasion and sentenced to two-and-a-half years’ in prison. Instead of being released at the end of his sentence in October 2010, he was held for further investigation. During this extended detention period, his family and lawyer were frequently refused permission to visit him and questions about his health condition – reportedly poor – were not answered. During the trial, Nguyen Van Hai reportedly stated that he had never acted against the state but was only “frustrated by injustice, corruption and dictatorship, which does not represent the state but some individuals.” He also insisted on the right to freedom of expression in accordance with international treaties to which Viet Nam is party. His 12-year prison sentence was upheld on appeal on 28 December 2012. In June 2013, he went on hunger strike in protest at the harsh treatment of himself and other political prisoners at Prison No 6 in Nghe An province. He ended the hunger strike after 38 days when he was informed by an official that his complaint would be investigated.

Ta Phong Tan (f), 45, is a former policewoman. She is a Redemptorist Catholic known as Maria Ta Phong Tan among her Catholic community. She was arrested in September 2011 and detained with limited access to her family and lawyer. Dang Thi Kim Lieng, Ta Phong Tan’s mother, died after setting herself on fire in front of the local People’s Committee Office on 30 July 2012 out of despair at the treatment of her daughter and her family who were being harassed by security forces. This caused the scheduled trial to be postponed for the third time. Ta Phong Tan was told about her mother’s death in prison, and was not allowed to attend her funeral ceremony. At the trial she was forcibly removed from the court when she became upset and tried to challenge the verdict. Her 10-year prison sentence was upheld on appeal on 28 December 2012.

Ta Phong Tan (f), 45, is a former policewoman. She is a Redemptorist Catholic known as Maria Ta Phong Tan among her Catholic community. She was arrested in September 2011 and detained with limited access to her family and lawyer. Dang Thi Kim Lieng, Ta Phong Tan’s mother, died after setting herself on fire in front of the local People’s Committee Office on 30 July 2012 out of despair at the treatment of her daughter and her family who were being harassed by security forces. This caused the scheduled trial to be postponed for the third time. Ta Phong Tan was told about her mother’s death in prison, and was not allowed to attend her funeral ceremony. At the trial she was forcibly removed from the court when she became upset and tried to challenge the verdict. Her 10-year prison sentence was upheld on appeal on 28 December 2012.

Phan Thanh Hai (m), 44, is a trained lawyer who was arrested in October 2010. His sentence was reduced to three years’ imprisonment on appeal, and he was released on 1 September 2013. He is now under house arrest.24

Dinh Dang Dinh (m), 50, is a former soldier and chemistry teacher who was living in Kien Duc, Dak R’Lap district of Dak Nong province in the Central Highlands, who became an environmental activist and blogger. He had initiated a petition against bauxite mining in the Central Highlands. He was arrested in December 2011, and sentenced by Dak Nong People’s Court to six years’ imprisonment in August 2012 under Article 88 for “conducting propaganda” against the state. He was accused of writing and posting anti-government documents on the internet and calling for democracy and pluralism. His trial lasted just three hours and the appeal hearing at which his sentence was upheld, only 45 minutes. On leaving the appeal court, he was manhandled into a truck and beaten over the head with clubs by security officials.

4.2 CATHOLIC SOCIAL ACTIVISTS AND BLOGGERS

- ACTIVISTS FROM VINH CITY, NGHE AN PROVINCE

In mid-2011, 17 social activists and bloggers, most of them Catholics in the diocese of Vinh city, the capital of Nghe An province in north central coastal Viet Nam, were arrested. Three of them were charged under Article 88 of the Penal Code (Conducting propaganda against the state) and tried by Nghe An People’s Court on 26 September 2012:

Chu Manh Son (m), 24, a student and Catholic social activist was arrested on 2 August 2011. He had taken part in anti-China protests. He was sentenced to three years’ imprisonment with one year under house arrest on release. The sentence was reduced to two and a half years’ imprisonment on appeal.

Dau Van Duong (m), 25, a tourism student was arrested on 2 August 2011. He had taken part in anti-China protests and supported dissident Cu Huy Ha Vu’s petition against bauxite mining in the Central Highlands. He also attended the trial of Cu Huy Ha Vu (see below). He was sentenced to three and a half years’ imprisonment with 18 months’ house arrest on release.

Tran Huu Duc (m), 25, a computer science student, was arrested on 2 August 2011. He had taken part in anti-China protests and supported dissident Cu Huy Ha Vu’s petition against bauxite mining in the Central Highlands. He also attended the trial of Cu Huy Ha Vu. He was sentenced to three years’ and three months’ imprisonment with one year under house arrest on release.

An additional 14 activists were charged for their alleged connection with or membership of Viet Tan, an overseas based group peacefully campaigning for democracy in Viet Nam, but described as a “reactionary” or “terrorist” organization by the government. All were charged under Article 79 of the Penal Code (“overthrowing” the state), and tried on 8 to 9 January 2013. Twelve of them remain imprisoned, while two others have been released:

Dang Ngoc Minh (f), 56, is a housewife arrested on 2 August 2011. She was sentenced to three years’ imprisonment with two years’ house arrest on release. She is the mother of Nguyen Dang Minh Man and Nguyen Dang Vinh Phuc who were tried at the same time.

Dang Xuan Dieu (m), 34, is an engineer, blogger and social activist arrested at Tan Son Nhat International airport, Ho Chi Minh City in July 2011. He was sentenced to 13 years’ imprisonment with five years’ house arrest on release.

Ho Duc Hoa (m), 39, a journalist, community organizer and company director was arrested on 2 August 2011. He was sentenced to 13 years’ imprisonment with five years’ house arrest on release.

Ho Van Oanh (m), 28, was a student at the time of his arrest on 16 August 2011. He was sentenced to three years reduced to two and a half years’ imprisonment on appeal, with three years’ house arrest on release.

Nguyen Dang Minh Man (f), 28, a freelance worker was arrested on 2 August 2011. She was sentenced to eight years’ imprisonment with five years’ house arrest on release;

Nguyen Dinh Cuong (m), 32, was the director of Canh Tan Company at the time of his arrest on 24 December 2011. He was sentenced to four years’ imprisonment with three years’ house arrest on release.

Nguyen Van Duyet (m), 32, a student at Huyen Mon church of Thanh Da was arrested on 7 August 2011. He was sentenced to four reduced to three and a half years’ imprisonment on appeal with four years’ house arrest on release.

Nguyen Van Oai (m), 32, an engineer unemployed at the time of his arrest on 9 August 2011. He was sentenced to three years’ imprisonment with two years’ house arrest on release.

Nong Hung Anh (m), 30, a foreign languages student, blogger and Presbyterian arrested on 5 August 2011. He was sentenced to five years’ imprisonment with three years’ house arrest on release.

Paulus Le Van Son (m), 28, blogger, journalist and community organizer arrested on 3 August 2011. He was sentenced to 13 years’ imprisonment under Article 79 with five years’ house arrest on release. His sentence was reduced to four years’ imprisonment on appeal in May 2013.

Thai Van Dung (m), 25, an English student, was arrested on 19 August 2011. He was sentenced to four years’ imprisonment under Article 79 with three years’ house arrest on release.

Tran Minh Nhat (m), 25, is a student of foreign languages and IT arrested on 27 August 2011. He was sentenced to four years’ imprisonment under Article 79 with three years’ house arrest on release.

Nguyen Vinh Phuc Dang (m), 33, a welder, was arrested on 2 August 2011. He was sentenced to three years’ imprisonment suspended and was released after the trial. Nguyen Xuan Anh (m), 31, a martial arts instructor, was arrested on 7 August 2011. He was sentenced to three years’, reduced to two years’ imprisonment on appeal, with two years’ house arrest on release. He should now be released and under house arrest.25

• CATHOLIC SUPPORTERS OF FATHER NGUYEN VAN LY

Two Catholics from the Vinh diocese were tried on 6 March 2012 by Nghe An Provincial People’s Court. Both are supporters of Father Nguyen Van Ly (see above section on pro-democracy activists) who at the time was temporarily released from prison on medical parole. They were accused of contacting Father Ly and printing and distributing leaflets in Nghe An province, and were arrested at an unknown date in 2011. They were charged with “conducting propaganda” against the state under Article 88 of the Penal Code:

Nguyen Van Thanh (m), 29, was sentenced to three years’ imprisonment.

Vo Thi Thu Thuy (f), 52, was sentenced to five years’ reduced to four years’ imprisonment on appeal.

4.3 HUMAN RIGHTS AND SOCIAL JUSTICE ACTIVISTS

Cu Huy Ha Vu (m), 55, is a human rights defender, legal scholar and environmental activist arrested in November 2010 in Ho Chi Minh City. He was sentenced to seven years’ imprisonment on 4 April 2011 by Ha Noi People’s Court under Article 88 of the Penal Code for “conducting propaganda” against the state. He had twice submitted criminal complaints against the Prime Minister, once in an attempt to stop a controversial bauxite mining project, and the other challenging the legality of a ban on class-action complaints. Cu Huy Ha Vu went on hunger strike in May 2013. He ended his protest after 25 days when he received a written response from the prison authorities to his complaints about the conditions of his detention.

Credit Dan Lam Bao

Ho Thi Bich Khuong (f), 46, has been an outspoken and peaceful activist for social justice for more than 20 years, after she and other stall holders were evicted from Cho Chua market in Nghe An province without compensation. Despite repeated intimidation and harassment, including arrest and imprisonment, she has submitted countless complaints to the local and national authorities about cases of injustice. She has written a blog and published accounts of human rights violations against the rural poor, and the harassment of her family and others. She has also taken part in protests about land rights, and is a supporter of Bloc 8406. 26 Ho Thi Bich Khuong was arrested in November 2010 for giving interviews to foreign media and distributing “anti-government” material. She was tried on 29 December 2011 by Nghe An People’s Court, and sentenced to five years’ imprisonment under Article 88 of the Penal Code for “conducting propaganda” against the state, with three years’ house arrest on release. She has been beaten in detention, including by other prisoners, sustaining injuries for which she has not received adequate medical treatment. Ho Thi Bich Khuong was previously imprisoned for two years under Article 258 of the Penal Code for “abusing democratic freedoms” after she was arrested at an internet café. During that prison term she wrote a diary which was published after her release; it gives an account of the harsh treatment she faced.

Le Quoc Quan (m), 42, is a prominent human rights lawyer and blogger. He was arrested on 27 December 2012 and tried on 2 October 2013 by Ha Noi People’s Court on politically motivated charges of tax evasion in connection with a consultancy business that he runs. He was sentenced to two and a half years’ imprisonment plus a heavy fine. Le Quoc Quan had previously been imprisoned without trial for three months in 2007. Then, he had just returned to Viet Nam from the USA where he had been on a fellowship with the National Endowment for Democracy for almost six months. Le Quoc Quan is a Catholic who blogged about human rights violations, as well as political and religious freedom. Prior to his arrest in December, he had faced considerable harassment and constant surveillance by the authorities. Other members of his family have also been targeted by he authorities.

Phan Ngoc Tuan (m), 54, is an advocate for religious, land and workers’ rights from Phan Rang-Thap Cham city, Ninh Thuan province. He was arrested on 10 August 2011 and tried by Ninh Thuan Provincial People’s Court on 7 June 2012. He was accused of being in contact with overseas groups. He was sentenced to five years’ imprisonment for “conducting propaganda” against the state under Article 88 of the Penal Code, with three years’ house arrest on release. The family of Phan Ngoc Tuan have reportedly been subjected to intense harassment and intimidation since his arrest.

4.4 LABOUR RIGHTS ACTIVISTS

- UNITED WORKERS-FARMERS ORGANIZATION (UWFO)

Three members of the UWFO – an independent labour organization not recognized by the authorities – were tried by a court in Tra Vinh province on 27 October 2010. The UWFO aims to protect and promote workers’ rights, including advocating for the right to form and participate in independent trade and labour unions. Independent trade unions are not allowed in Viet Nam. The three activists were charged under Article 89 (Disrupting security) of the Penal Code. All were arrested in February 2010 after handing out leaflets at a shoe factory in Tra Vinh province, where they were supporting workers demanding better pay and working conditions.

Do Thi Minh Hanh (f), 28, has been a labour activist for 10 years and is also a member of “Victims of Injustice”, a petitioners’ movement claiming redress for complaints against the authorities. She was sentenced to seven years’ imprisonment. She has been subjected to harsh treatment in detention, including beatings by fellow prisoners, and has not received adequate medical care.

Doan Huy Chuong (m), 28, a labour organizer and founding member of UWFO, was also sentenced to seven years’ imprisonment. He was beaten during pre-trial detention. He previously spent 18 months in prison between 2007 and 2008 on charges of “abusing democratic freedoms” under Article 258 of the Penal Code.

Nguyen Hoang Quoc Hung (m), 32, is a labour organizer and member of “Victims of Injustice”. He was sentenced to nine years’ imprisonment. He was beaten during pre-trial detention but refused to plead guilty to the charges against him. He is in poor health.

4.5 LAND RIGHTS ACTIVISTS

- LAND PROTESTERS IN BAC GIANG PROVINCE

Three land activists were tried on 16 July 2012 by Bac Giang Provincial People’s Court. They were charged with “conducting propaganda” against the state under Article 88 of the Penal Code. The three had peacefully protested and made complaints on behalf of farmers about official corruption involving land. They were also accused of distributing information critical of the government, and inciting people to take part in anti-China protests.

Dinh Van Nhuong (m), 54, was sentenced to four years’ imprisonment with three years’ house arrest on release.

Do Van Hoa (m), 46, was sentenced to four years’ imprisonment with three years house arrest on release.

Nguyen Kim Nhan (m), 53, was the leader of land protests in Bac Giang province. He was sentenced to five and a half years’ imprisonment with four years’ house arrest on release.

Nguyen Ngoc Cuong (m), 57, is a land rights activist arrested in April 2011, with his son, Pham Thi Bich Chi and daughter-in-law, Nguyen Ngoc Tuong Thi. They were accused of distributing anti-government leaflets and creating an internet forum “Viet Nam and current issues” to encourage activism. They were tried on 21 October 2011 under Article 88 of the Penal Code for “conducting propaganda” against the state. Nguyen Ngoc Cuong was sentenced to seven years’ imprisonment; his son to two years’ imprisonment and his daughter-in-law received a one-and-a-half year suspended sentence.

Pham Thi Bich Chi (m) and Nguyen Ngoc Tuong Thi (f) are now released but under house arrest. 27

- LAND RIGHTS ACTIVISTS IN BEN TRE PROVINCE

Two women and five male land rights activists were tried by Ben Tre Provincial People’s Court on 30 May 2011. According to the indictment, they are all accused of having joined or been associated with Viet Tan, an overseas-based group peacefully campaigning for democracy in Viet Nam. The Vietnamese authorities describe Viet Tan as a “reactionary” organization in exile, or a “terrorist” group. The seven were charged under Article 79 of the Penal Code for “activities aimed at overthrowing” the state. The UNWGAD adopted Opinion No 46/201128 on 2 September 2011 that the detention of the seven activists is arbitrary and should be remedied by their release and compensation.

Tran Thi Thuy (f), 42, is a trader, Hoa Hao Buddhist and land rights activist for farmers whose land has been confiscated. She was arrested in August 2010 and sentenced to eight years’ imprisonment, with five years’ house arrest on release.

Pham Van Thong (m), 51, a farmer and land rights activist was arrested in July 2010. He was sentenced to seven years’ imprisonment, with five years’ house arrest on release.

Duong Kim Khai (m), 55, is Pastor of the Cowshed Mennonite house church and a land rights activist. He helped farmers to petition the authorities about land confiscation. He was arrested in August 2010 and sentenced to six years, reduced to five years’ imprisonment on appeal, with five years’ house arrest on release.

Cao Van Tinh (m), 39, is a farmer and land rights activist who had taken part in protests in Ho Chi Minh City. He was arrested in February 2011. He was sentenced to five years’, reduced to four and a half years’ imprisonment on appeal.

Pham Ngoc Hoa (f), Nguyen Thanh Tam (m) and Pastor Nguyen Chi Thanh (m) received two-year prison sentences and are now released but under house arrest. 29

4.6 POLITICAL ACTIVISTS

Le Thanh Tung (m), 48, is a supporter of Bloc 8406 and blogger advocating pluralism and constitutional changes. He was arrested in December 2011 and tried by Ha Noi People’s Court on 10 August 2012 under Article 88 of the Penal Code for “conducting propaganda” against the state. He received a five-year sentence, reduced to four years’ imprisonment on appeal, and four years’ house arrest on release. According to state-controlled media, he was accused of writing and posting articles on the internet from August 2009 to October 2011 that “distorted the truth” about the authorities and society, and of “sabotaging” the National Party Congress and elections to the National Assembly and People’s Councils.

Lo Thanh Thao (f), 36, from Dong Nai province was arrested on 26 March 2012. She was accused of scattering anti-government leaflets outside buildings in Ho Chi Minh City. The authorities claimed that she had acted on the instructions of an overseas Vietnamese person in the USA. On 8 January 2013, Ho Chi Minh City People’s Court sentenced her to three and a half years’ imprisonment under Article 88 of the Penal Code (“conducting propaganda” against the state), with two years’ house arrest on release.

- LU VAN BAY, ALSO KNOWN AS TRAN BAO VIET

Lu Van Bay aka Tran Bao Viet (m), 61, is a pro-democracy activist and writer. In 2007 he was accused of writing eight articles advocating a multi-party system which were published on an overseas Vietnamese website “Voice of Freedom”. He was detained for questioning and released after being told not to write further. He was re-arrested on 26 March 2011 after security officials seized his computer and articles from his home. He was accused of writing 16 articles under the pen-name Tran Bao Viet which criticized the ruling Communist Party of Viet Nam (CPV) and called for a multi-party system. Lu Van Bay was tried by a court in Tan Hiep, Kien Giang province on 22 August 2011 and sentenced to four years’ imprisonment for “conducting propaganda” against the state, with three years’ house arrest on release. He is a former army officer who was previously imprisoned between 1977 and 1983 for “counter-revolutionary” activities.

Ngo Hao (m), 65, is a former army officer, arrested on 8 February 2013. He was accused of writing articles on the internet critical of Viet Nam’s government and the ruling CPV, and of supporting Bloc 8406. In an appeal letter written before his trial, his wife said that he had only informed friends and others about injustices, particularly against religious figures facing persecution. He was tried by Phu Yen Provincial People’s Court on 11 September 2013, charged with aiming to “overthrow” the government under Article 79 of the Penal Code. He was sentenced to 15 years’ imprisonment, with five years’ house arrest on release. He is in poor health.

Dinh Nguyen Kha (m), 25, a student and computer repairer, is one of two young activists convicted of “conducting propaganda” against the state under Article 88 of the Penal Code by a court in Long An province on 16 May 2013. He was arrested on 11 October 2012 and accused of distributing leaflets critical of the government. The leaflets criticised the reaction of the government to China’s alleged territorial claims and policies that affect Viet Nam, such as in the South China Sea/East Sea. He was sentenced to eight years’ imprisonment in the first instance, reduced to four years in prison on appeal by Ho Chi Minh Supreme People’s Court on 16 August 2013.

Nguyen Phuong Uyen (f), 21, is also a student and was tried with Dinh Nguyen Kha. She was arrested on 14 October 2012, and held for several days without informing her family where she was. She was sentenced to six years’ imprisonment in the first instance. Her sentence was reduced on appeal to a three year suspended sentence, with 52 months’ probation. She has been released from prison, but has faced violent harassment from security officials.

Prior to the beginning of her suspended sentence on 25 September 2013, Nguyen Phuong Uyen, her mother and another blogger visited Ha Noi and other places. On the evening they were due to fly back home, they and others were having dinner at blogger Nguyen Tuong Thuy’s house when police interrupted and violently arrested all those present. Nguyen Phuong Uyen and her mother were taken to a local police station and then to the airport, where Uyen was hit by security staff and police, and subjected to sexual harassment. They were eventually allowed to leave. The others arrested were later released without charge. 30

Dinh Nhat Uy (m), 30, is a blogger and elder brother of Dinh Nguyen Kha. He was arrested on 15 June 2013 and charged under Article 258 for “abusing democratic freedoms” for his writing and calling for his brother’s release. On 29 October 2013, a court in Long An province sentenced him to 15 months’ suspended imprisonment and one year under house arrest at the end of the 15 months. He was released from prison.31

Nguyen Tien Trung (m), 30, an IT engineer, blogger and pro-democracy activist, was arrested in July 2009. He studied Information Technology in France for five years, where he co-founded with friends the Assembly of Vietnamese Youth for Democracy in 2006. The Assembly was a group that encouraged young Vietnamese people abroad and in Viet Nam to call for political reform and democracy. On graduating and finishing his studies in France, Trung returned to Viet Nam in August 2007. In March 2008, Trung was called up for military service. Because of his political beliefs, he refused to swear the Army’s oath because it implied loyalty to the ruling Communist Party of Viet Nam. This led to his discharge.

Nguyen Tien Trung (m), 30, an IT engineer, blogger and pro-democracy activist, was arrested in July 2009. He studied Information Technology in France for five years, where he co-founded with friends the Assembly of Vietnamese Youth for Democracy in 2006. The Assembly was a group that encouraged young Vietnamese people abroad and in Viet Nam to call for political reform and democracy. On graduating and finishing his studies in France, Trung returned to Viet Nam in August 2007. In March 2008, Trung was called up for military service. Because of his political beliefs, he refused to swear the Army’s oath because it implied loyalty to the ruling Communist Party of Viet Nam. This led to his discharge.

On 20 January 2010, he was tried with three others for attempting to “overthrow the people’s administration” under Article 79 of the Penal Code. He was sentenced to seven years’ imprisonment with three years’ house arrest on release. In August 2012, the UNWGAD adopted Opinion No 27/2012 on Nguyen Tien Trung and his three co-defendants, finding their detention to be arbitrary. The WGAD requested Viet Nam’s government to take steps to remedy the situation in accordance with the UDHR and the ICCPR to which Viet Nam is a state party. They called for the release of Nguyen Tien Trung and the three others, and for compensation to be made.

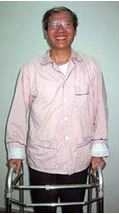

Father Nguyen Van Ly on the day he was released “temporarily” for medical treatment, March 2010. © Private.

Father Nguyen Van Ly (m), 67, is a Catholic priest and co-founder of Bloc 8406. He has spent around 20 years in prison because of his peaceful activism on human rights and criticism of government policies. He is currently serving an eight-year prison sentence imposed in March 2007, with five years’ house arrest on release. He was arrested in February 2007 and charged with “conducting propaganda” against the state under Article 88 of the Penal Code. Accusations against him included involvement in the internet-based pro-democracy movement Bloc 8406, which he co-founded; taking part in the establishment of banned political groups; and publication of a dissident journal Tu Do Ngon Luan (Freedom and Democracy). Father Ly founded the Viet Nam Progression Party (VNPP) in September 2006 which advocated, amongst other things, for democracy and human rights. In March 2010, Father Ly was granted “temporary parole” to obtain medical treatment for serious health problems. In November 2009, Father Ly had a stroke which went undiagnosed in prison, and for which he did not receive proper medical care. The stroke caused partial paralysis. He was also diagnosed to have a brain tumour. Despite not being fully recovered and in poor health, Father Ly was returned to prison on 25 July 2011 – the authorities claimed that he had distributed anti-government leaflets during his parole.

On 3 September 2010, the UNWGAD issued Opinion No 14/2010, in which it stated that Father Ly’s detention was arbitrary and in violation of numerous articles in the UDHR and the ICCPR. The UNWGAD requested that he be immediately released and provided with adequate reparations.

ather Ly was previously jailed for one year between 1977 and 1978, and for a further nine years between May 1983 and July 1992, after being sentenced for “opposing the revolution and destroying the people’s unity.” He was arrested again in 2001 and sentenced to 15 years’ imprisonment. He was released under a prisoner amnesty in February 2005. During his imprisonment, he has at times being held in solitary confinement for lengthy periods.

Nguyen Xuan Nghia (m), 64, is a writer and supporter of Bloc 8406 arrested in September 2008. He was sentenced to six years’ imprisonment for “conducting propaganda” against the state under Article 88 of the Penal Code, with three years’ house arrest on release. He was accused of hanging anti-government banners on a flyover during an anti-China protest when the Olympic Torch passed through Ho Chi Minh City. He suffers from medical conditions – haemorrhoids and a prostatic tumour – that require treatment; in November 2012 he was admitted to hospital for surgery. In September 2013, Nguyen Xuan Nghia was reportedly beaten by a fellow inmate.

Two songwriters were tried on 30 October 2012 by Ho Chi Minh City People’s Court on charges of “conducting propaganda” against the state under Article 88 of the Penal Code. Both criticised China’s territorial claims in the disputed South China Sea/East Sea – and Viet Nam’s response to these claims. They also highlighted issues of social justice and human rights.

Tran Vu Anh Binh, also known as Hoang Nhat Thong, 39, was arrested in September 2011 and sentenced to six years’ imprisonment, with two years’ house arrest on release;

Vo Minh Tri, also known as Viet Khang, 41, was first arrested in September 2011, then released and re-arrested in December 2011. He was sentenced to four years’ imprisonment, with two years’ house arrest on release.

Tran Anh Kim, 64, a writer and former officer in the Vietnamese People’s Army, was arrested in July 2009. He is a supporter of Bloc 8406, and Deputy Secretary General of the banned Democratic Party of Viet Nam. He had circulated petitions protesting about injustice and corruption in the ruling Communist Party of Viet Nam, and was accused of posting anti-government articles on the Internet and giving interviews to foreign media. He was tried on 28 December 2009 by Thai Binh People’s Court and sentenced to five and half years’ imprisonment under Article 79 of the Penal Code, with three years’ house arrest on release.

Tran Huynh Duy Thuc (m), 47, an entrepreneur, blogger and human rights defender, was arrested in May 2009. He is an advocate of economic, social and administrative reform, and respect for human rights. He began blogging under the pen name of Tran Dong Chan after he received no response to letters he had written to senior government officials. In 2008, he began co-writing “The Path of Viet Nam” – an assessment of the current situation in Viet Nam, with a comprehensive set of recommendations for governance reform, focusing on: the economy, education, administrative reform and the legal sector, with respect for human rights at the centre. He was initially accused of “theft of telephone wires” before being charged under Article 88 for “conducting propaganda” against the state. However, he was tried by Ho Chi Minh City People’s Court on 20 January 2010 under Article 79 of the Penal Code (“attempting to overthrow” the state) and sentenced to 16 years’ imprisonment with five years’ house arrest on release. During the trial he declared that he was tortured while in detention to force him to confess. According to witnesses, the judges deliberated for only 15 minutes before returning with the judgment, which took 45 minutes to read, suggesting it had been prepared in advance of the hearing.

Tran Huynh Duy Thuc (m), 47, an entrepreneur, blogger and human rights defender, was arrested in May 2009. He is an advocate of economic, social and administrative reform, and respect for human rights. He began blogging under the pen name of Tran Dong Chan after he received no response to letters he had written to senior government officials. In 2008, he began co-writing “The Path of Viet Nam” – an assessment of the current situation in Viet Nam, with a comprehensive set of recommendations for governance reform, focusing on: the economy, education, administrative reform and the legal sector, with respect for human rights at the centre. He was initially accused of “theft of telephone wires” before being charged under Article 88 for “conducting propaganda” against the state. However, he was tried by Ho Chi Minh City People’s Court on 20 January 2010 under Article 79 of the Penal Code (“attempting to overthrow” the state) and sentenced to 16 years’ imprisonment with five years’ house arrest on release. During the trial he declared that he was tortured while in detention to force him to confess. According to witnesses, the judges deliberated for only 15 minutes before returning with the judgment, which took 45 minutes to read, suggesting it had been prepared in advance of the hearing.

In August 2012, the UNWGAD adopted Opinion No 27/2012 concerning Tran Huynh Duy Thuc and his three co-defendants. The Working Group concluded his detention was arbitrary and requested the government of Viet Nam to release him and provide compensation.

Vi Duc Hoi (m), 56, a writer and supporter of Bloc 8406, was arrested in October 2010. He was a member of the ruling Communist Party of Viet Nam until he was expelled in 2007 for calling for democratic reform. He was accused of using the internet to promote democracy and charged under Article 88 of the Penal Code (“conducting propaganda” against the state). On 26 January 2011, Lang Son People’s Court sentenced him to eight years’ imprisonment with five years’ house arrest on release. His sentence was reduced on appeal in April 2011 to five years’ imprisonment and three years’ house arrest on release.

4.7 RELIGIOUS FOLLOWERS

Nguyen Cong Chinh (m) also known as Nguyen Thanh Long, 44, is a Mennonite pastor arrested in April 2011 in Pleiku, Gia Lai province in the Central Highlands. He was sentenced to 11 years’ imprisonment on 26 March 2012 by a court in Pleiku for “undermining the national unity policy” under Article 87 of the Penal Code. According to Pastor Chinh’s wife, she was not allowed to visit him until 18 months after his arrest. He was accused of giving interviews to foreign media and joining with other dissidents, namely – Father Nguyen Van Ly, Nguyen Van Dai, Le Thi Cong Nhan, Tran Khai Thanh Thuy – to oppose the authorities and incite complaints. Pastor Chinh complained that he had faced harassment from the authorities since 2003 and had to move from one church to another.

Venerable Thich Quang Do (m), 85, is the Supreme Patriarch of the banned Unified Buddhist Church of Viet Nam (UBCV). He has been imprisoned, arbitrarily detained or held under house arrest intermittently since the early 1990s. In October 2003, while returning to Ho Chi Minh City with other Buddhist monks from a UBCV meeting in another province, security officials told him that he had been placed in administrative detention for an indefinite period at his pagoda. Since then he has been held under constant police surveillance at the Thanh Minh Zen monastery in Ho Chi Minh City. Police officials have harassed and turned away some overseas visitors, including members of the European Parliament.

Thich Quang Do suffers from diabetes and high blood pressure. The authorities do not ensure that he is regularly provided with proper medical care, medication or opportunity for exercise, which is taking a toll on his health. 32

- MEMBERS OF THE HOA HAO BUDDHIST CHURCH

Members of the “traditional” branch of the Hoa Hao Buddhist church not recognized by the authorities face harassment and interference by local security officials when holding religious ceremonies.

Bui Van Tham (m), 27, and Bui Van Trung (m), were both charged under Article 257 of the Penal Code (“Resisting persons in the performance of their official duties”), and tried by the Anh Phu District People’s Court in An Giang province. Bui Van Tham was arrested in June 2012 and sentenced to two and half years in prison in September 2012, while Bui Van Trung, the father of Bui Van Tham, was arrested in October 2012 and sentenced to four years’ imprisonment on 23 January 2013.

In a separate case, two Hoa Hao Buddhists Nguyen Van Lia and Tran Hoai An were tried by Cho Moi People’s Court in An Giang province on 2 March 2012 under Article 258 of the Penal Code for “abusing democratic freedoms”.

Nguyen Van Lia (m), 73, was arrested in April 2011 with his wife, who was subsequently released. He is a well known advocate for the “traditional” branch of the Hoa Hao Buddhist church. He was accused of distributing anti-government leaflets and CDs which contained information on human rights violations by the authorities. He and Tran Hoai Anh are also accused of providing foreign media and foreign religious delegations with information about religious repression. He received a five-year sentence reduced to four and a half years’ imprisonment on appeal, and three years’ house arrest on release. He had previously spent one and a half years in prison in 2003-4 after being tried for taking part in a religious ceremony for the church founder. He is in poor health, and has lost most of his hearing.

Tran Hoai An (m), 62, was arrested in February 2011. He was accused of distributing anti-government leaflets and CDs which contained information on human rights violations by the authorities, and of meeting with foreign delegations to inform them about religious repression. He was sentenced to three years’ imprisonment with two years’ house arrest on release.

- RELIGIOUS ENVIRONMENTAL GROUP IN PHU YEN PROVINCE

The “Council for the Laws and Public Affairs of Bia Son” (Hoi dong Cong luan Cong an Bia Son) are a little known peaceful religious group dedicated to protecting the environment, who had set up an eco-tourism company in Phu Yen province. State-controlled media described them as a political group with 300 members using “non-violent subversion” to criticize government policies and establish a “new state”. Twenty-two Council members were arrested in February 2012 and tried under Article 79 by Phu Yen People’s Court on 28 January 2013. They received harsh prison sentences; all except Phan Van Thu were also sentenced to five years’ house arrest on release.

Phan Van Thu (m), 65, the founder of the Council was sentenced to life imprisonment; Le Duy Loc (m), 57, Council member sentenced to 17 years’ imprisonment;

Vuong Tan Son (m), 60: Council member sentenced to 17 years’ imprisonment; Nguyen Ky Lac (m), 62, Council member sentenced to 16 years’ imprisonment; Doan Dinh Nam (m), 62, Council member sentenced to 16 years’ imprisonment; Ta Khu (m), 66, Council member sentenced to 16 years’ imprisonment;

Tu Thien Luong (m), 63, Council member sentenced to 16 years’ imprisonment’ Vo Ngoc Cu (m), 62, Council member sentenced to 16 years’ imprisonment;

Vo Thanh Le (m), 58, Council member sentenced to 16 years’ imprisonment; Vo Tiet (m), 61, Council member sentenced to 16 years’ imprisonment;

Le Xuan Phuc (m), 62, Council member sentenced to 15 years’ imprisonment; Doan Van Cu (m), 51, Council member sentenced to 14 years’ imprisonment; Nguyen Dinh (m), 45, Council member sentenced to 14 years’ imprisonment; Phan Thanh Y (m), 65, Council member sentenced to 14 years’ imprisonment; Do Thi Hong (f), 56, Council member sentenced to 13 years’ imprisonment; Tran Phi Dung (m), 47, Council member sentenced to 13 years’ imprisonment; Le Duc Dong (m), 30, Council member sentenced to 12 years’ imprisonment Le Trong Cu (m), 47, Council member sentenced to 12 years’ imprisonment;

Luong Nhat Quang (m), 26, Council member sentenced to 12 years’ imprisonment; Nguyen Thai Binh (m), 27, Council member sentenced to 12 years’ imprisonment; Tran Quan (m), 29, Council member sentenced to 12 years’ imprisonment;

Phan Thanh Tuong (m), 26, Council member sentenced to 10 years’ imprisonment.

5. CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATIONS

“Vietnam is a country under the rule of law. Vietnam handles acts that violate the law and undermine the national security to protect the rule of law and safeguard the common society interests of peace, stability and development. The legal proceedings of detention, investigation, trial and conviction have been conducted on the guilty offenders, in according with Vietnamese law, completely in line with international law.”

Ministry of Foreign Affairs Spokesperson response to criticism over the trial and conviction of prisoners of conscience Le Cong Dinh, Le Thanh Long, Nguyen Tien Trung, and Tran Huynh Duy Thuc in January 2010.33

Contrary to statements made by Viet Nam government officials, such as in the quote above, the arrest, imprisonment for lengthy periods of time, and restriction under house arrest of scores of peaceful activists, human rights defenders and religious followers is in violation of Viet Nam’s obligations under the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR).

In line with Viet Nam’s commitment to respect the rule of law, and as it seeks to play an increasing role on the international scene including at the Human Rights Council, it is essential that the authorities demonstrate full respect and commitment to the protection of human rights defenders and other peaceful activists and individuals in Viet Nam. In particular, Viet Nam’s government should adopt a comprehensive plan to ensure that peaceful activists and religious followers have the space to carry out their activities, and that they are no longer at risk of harassment, arrests, detention and imprisonment in harsh conditions simply for peacefully exercising their human rights.

In order to improve respect for the right to free speech in Viet Nam and to ensure that human rights defenders and other activists are able to freely express their opinions and beliefs, Amnesty International recommends that Viet Nam’s government, and in particular the Prime Minister, the Minister of Public Security, the Minister of Justice, and the Law Committee of the National Assembly:

Release immediately and unconditionally all prisoners of conscience, whether they are in pre-trial detention, imprisoned after conviction by a court, or under house arrest;

Ensure that all those released are able to effectively access their right to remedy in accordance with international law, and that they are provided with reparations for their suffering;

Publicly commit to respecting the right to freedom of expression, and in particular commit to respecting and promoting the UN General Declaration on Human Rights Defenders;

Take measures to ensure that human rights defenders, peaceful activists and religious followers are free from violence, discrimination and the threat of criminalisation;

Take steps to ensure that non state actors who may have used violence against human rights defenders are brought to justice in proceedings that meet international fair trial standards without recourse to the death penalty;

Repeal or else amend provisions in the 1999 Penal Code to ensure that ambiguous provisions relating to national security are clearly defined or removed, so they cannot be applied in an arbitrary manner to stifle legitimate and peaceful dissent, debate, opposition and freedom of expression;

Ensure that the Internet decrees, the Press law, the January 2011 Decree No.1/2011 on administrative sanctions in the press and publication field, the Publishing Law, and the State Secrets Protection Ordinance are in line international human rights law and standards, including provisions contained in the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR);

Ensure that the revised draft constitution recognizes the rights provided for in Articles 19, 21, and 22 of the ICCPR in terms fully consistent with those articles and that it does not circumvent Viet Nam’s international human rights obligations as a state party;

Undertake reform of the courts and judiciary to ensure independence from the government, and to ensure that international fair trial guarantees are respected;

Ratify the First Optional Protocol to the ICCPR to allow individuals to submit complaints to the Human Rights Committee of violations of the rights set out in the Covenant;

Ensure that the definition of torture as provided for under the Convention Against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment of Punishment (UNCAT) is fully incorporated within national legislation with adequate penalties, and ratify the UNCAT at the earliest opportunity; and

Issue a standing invitation to UN Special Procedures, including the Special Rapporteur on freedom of opinion and expression; the Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights defenders; the Special Rapporteur on the rights to freedom of peaceful assembly and of association; the Special Rapporteur on Torture, and the Working Group on Arbitrary Detention.

Amnesty International also recommends that other governments and donors:

Undertake regular visits of prisoners of conscience in Viet Nam, and call for their immediate and unconditional release;

Encourage Viet Nam to take concrete steps to ensure that human rights defenders, peaceful activists and religious followers are free from violence, discrimination and the threat of criminalisation; and

Support Viet Nam’s legal reform process, and in particular support full compliance between national legislation and international human rights law and standards such as provisions set out in the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights.

APPENDIX 1: ARTICLES OF THE 1999 PENAL CODE USED TO IMPRISON ACTIVISTS AND OTHERS

CHAPTER XI: CRIMES OF INFRINGING UPON NATIONAL SECURITY

Article 79: Carrying out activities aimed at overthrowing the people’s administration.

Those who carry out activities, establish or join organizations with intent to overthrow the people’s administration shall be subject to the following penalties:

1) Organizers, instigators and active participants or those who cause serious consequences shall be sentenced to between 12 and 20 years of imprisonment, life imprisonment or capital punishment;

2) Other accomplices shall be subject to between five and 15 years of imprisonment.

Article 87: Undermining the unity policy.

1) Those who commit one of the following acts with a view to opposing the people’s administration shall be sentenced to between five and 15 years of imprisonment.

a. Sowing division among people of different strata, between people and the armed forces or the people’s administration or social organizations;

b. Sowing hatred, ethnic bias and/or division, infringing upon the rights to equality among the community of Vietnamese nationalities;

c. Sowing division between religious people and non-religious people, division between religious believers and the people’s administration or social organizations;

d. Undermining the implementation of policies for international solidarity.

2) In the case of committing less serious crimes, the offenders shall be sentenced to between two and seven years of imprisonment.

Article 88: Conducting propaganda against the Socialist Republic of Viet Nam.

1) Those who commit one of the following acts against the Socialist Republic of Viet Nam shall be sentenced to between 10 and 20 years of imprisonment:

a. Propagating against, distorting and/or defaming the people’s administration;

- b. Propagating psychological warfare and spreading fabricated news in order to foment confusion among people;

- c. Making, storing and/or circulating documents and/or cultural products with contents against the Socialist Republic of Viet Nam.

2) In the case of committing less serious crimes, the offenders shall be sentenced to between three and 12 years of imprisonment.

Article 89: Disrupting security.

1) Those who intend to oppose the people’s administration by inciting, involving and gathering many people to disrupt security, oppose officials on public duties, obstruct activities of agencies and/or organizations, which fall outside the cases stipulated in Article 82 [Rebellion] of this Code, shall be sentenced to between five and 15 years of imprisonment.

2) Other accomplices shall be sentenced to between two and seven years of imprisonment.

Article 92: Additional penalties.

Persons who commit crimes defined in this Chapter shall also be deprived of a number of civic rights for between one year and five years, subject to probation, residence ban for between one year and five years, confiscation of part or whole of the property.

CHAPTER XX: CRIMES OF INFRINGING UPON ADMINISTRATIVE MANAGEMENT ORDER

Article 257: Resisting persons in the performance of their official duties.

1) Those who use force, threaten to use force or use other tricks to obstruct persons in the performance of their official duties or coerce them to perform illegal acts, shall be sentenced to non-custodial reform for up to three years or between six months and three years of imprisonment.

2) Committing the offense in one of the following circumstances, the offenders shall be sentenced to between two and seven years of imprisonment:

a. In an organized manner;

b. Committing the offense more than once;

c. Instigating, inducing, involving, inciting other persons to commit the offense; d. Causing serious consequences;

e. Constituting a case of dangerous recidivism.

Article 258: Abusing democratic freedoms to infringe upon the interests of the State, the legitimate rights and interests of organizations and/or citizens.