They are afraid that when a religion becomes a big organization it will have a large impact on people. They have a dictatorial party, and they don’t want any other forces that have the ability to govern people.”

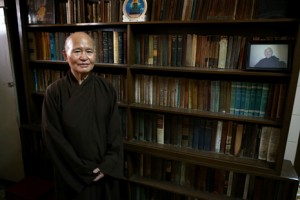

Thich Quang Do, inside the temple compound in Ho Chi Minh City where he has been under house arrest since 2003

Ucanews | March 27, 2014

Thich Quang Do’s only crime against the state is his religious belief

The small temple compound on the edge of downtown Ho Chi Minh City is Thich Quang Do’s world, and has been for more than a decade. The men who perch on motorbikes across the road from the temple are there every day, plain-clothed spooks who keep watch on his every move, logging details about the handful of visitors who come and go each year, and trailing the 87-year-old on the rare occasions he is permitted to leave for hospital.

The famed leader of the Unified Buddhist Church of Vietnam (UBCV) pities the men. “Many of the secret police have families to support so they are compelled to follow the communists. I think some of them don’t support the government’s ideology; they just support their families.” He’s grown used to the round-the-clock surveillance. His ongoing spell under house arrest in the Thanh Minh Zen Monastery is just the latest in a long line of incarcerations beginning in 1975, when the communist government consolidated control over South Vietnam, rounded up critics and put them behind bars.

The relationship between communism and religion has always been a hostile one, and no less so in Vietnam, where the government touts the merits of atheism above all other belief systems. It’s had a hard job enforcing this, however – the Pew Forum on Religion and Public Life counts 16 percent of the population as Buddhists, and eight percent as Christians; religions like Hoa Hao and Cao Dai that evolved locally are also popular. Yet believers need a thick skin – in its annual report last year, the US Commission on International Religious Freedom found freedom of belief to be “very poor” in Vietnam, with the government using a “specialized religious police force and vague national security laws” to suppress the ability to worship.

That apparatus of intimidation and surveillance, refined over nearly half a century of communist rule, has kept Thich Quang Do, as well as his colleagues, in a never-ending cycle of detention. The UBCV, formed in 1964, has been consistently critical of the government, and unlike the officially sanctioned Buddhist Sangha of Vietnam, has never been able to exist as an official entity. Other attempts by religious groups to organize beyond the government’s reach have been snuffed out: in January, the leader of the Buddhist Youth Movement, Le Cong Cau, boarded a plane bound for Ho Chi Minh City, where he planned to meet Thich Quang Do, and was detained. He is now under house arrest.

Although considered a dissident, Thich Quang Do is steadfastly apolitical. Yet with the line between politics and religion in an atheistic, authoritarian state forever thin, the government considers him a thorn in the elite’s side. “I must have the right to carry out our religious activities, but here, the Communist Party does not allow us to do as we want. I am not allowed to speak to the Buddhists, to explain Buddhist doctrine. They want to control everything we do, but we refuse.”

Driving around Ho Chi Minh City and its satellite towns, one could be forgiven for thinking that religious freedom is flourishing. In nearby Bien Hoa, a large Christian community makes use of the dozen or so gaudy and cavernous churches that line the main strip, some of which were built after the Communist Party took power. Worshippers breeze around the grounds of the Most Holy Redeemer church in central Ho Chi Minh City, seemingly at ease with the state of affairs in the country. In his office inside the church compound, however, Father Joseph Thoai, a Redemptorist priest, gestures towards the men at the main gate, who also quietly record who enters and leaves.

“No one has ever been able to destroy religion, because wherever man exists, religion exists,” Father Joseph says. Instead, the government seeks to curb its development. ”They are afraid that when a religion becomes a big organization it will have a large impact on people. They have a dictatorial party, and they don’t want any other forces that have the ability to govern people.”

The Redemptorists have had a similarly acrimonious relationship with Hanoi, and for decades have been vocally critical of government-sanctioned confiscation of church-owned land and property. Outside his office, a group of 20 or so people, all victims of land grabs, queue to seek advice on lodging complaints. Reports of police assaults and arbitrary arrests of Redemptorists are common – Father Joseph has been arrested twice recently, in 2011 and 2013, the latter when he attended the trial of blogger Dinh Nhat Huy. His colleague, Father Anthony, has been severely beaten by police in the past.

The government faces an uphill struggle in containing the spread of dissent, whether it be from a religious source or a political one. Freedom of religion is written into Vietnam’s constitution, Father Joseph notes, but that document unraveled long ago. Religious and political leaders are regularly slandered by the government in an effort to discredit them in the eyes of followers: in February, a court in Hanoi upheld the conviction of Le Quoc Quan, an anti-government Catholic blogger and lawyer, on highly spurious charges of tax evasion. Rights groups across the world have called for his release.

But the upsurge in arrests of dissidents over the past few years can be read as a sign that people are growing increasingly outspoken, and utilizing resources like the internet that the government struggles to control. Ten years ago, no one dared speak out, says Thich Quang Do, but that’s beginning to change.

“Time has passed, and people can use TV and know so much about the rest of the world; 20 years ago they only knew about what was happening in Vietnam. They were like birds in a cage,” he says with a smile and air of nonchalance that belies the stoicism that has kept him sane during his 40 years as a prisoner. “The government cannot control all the people easily, although they know that if they use their freedom to express their own ideas regarding politics, economics, religion, and so on, they must accept to go to jail.”

Rather than fearing the punishments the government could mete out to him for talking to visiting journalists, he welcomes the opportunity to speak. “They can put me in prison any time they want. I’m not afraid, so they need not send me to jail. I’m too old – if I die in prison it will not look good to the outside world.”

The government appears now to recognize this. The iconic monk has been nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize on numerous occasions; already feeling the weight of pressure over the spate of jail terms handed to dissidents in the past year’s crackdown, the government would rather a globally recognized figure be given at least the veneer of limited freedom in his temple compound.

Thich Quang Do may well remain in the temple until he, or the government, moves on. He’s just not sure who will go first. “Willy or nilly they must loosen political control – many people now are asking for democracy in Vietnam, and in the end, if the Communist Party wants to exist, it must change. Everything is changing each day – politics especially, always changing. Some day in the future they must accept other views, other parties. I think so, I want so.”

Height Insoles: Hi, I do believe this is an excellent site. I stumbledupon …

http://fishinglovers.net: Appreciate you sharing, great post.Thanks Again. Keep writi…

Achilles Pain causes: Every weekend i used to pay a quick visit this site, as i w…

March 28, 2014

The Vietnamese Buddhist leader whose temple is his prison

by Nhan Quyen • Thich Quang Do

Thich Quang Do, inside the temple compound in Ho Chi Minh City where he has been under house arrest since 2003

Ucanews | March 27, 2014

Thich Quang Do’s only crime against the state is his religious belief

The small temple compound on the edge of downtown Ho Chi Minh City is Thich Quang Do’s world, and has been for more than a decade. The men who perch on motorbikes across the road from the temple are there every day, plain-clothed spooks who keep watch on his every move, logging details about the handful of visitors who come and go each year, and trailing the 87-year-old on the rare occasions he is permitted to leave for hospital.

The famed leader of the Unified Buddhist Church of Vietnam (UBCV) pities the men. “Many of the secret police have families to support so they are compelled to follow the communists. I think some of them don’t support the government’s ideology; they just support their families.” He’s grown used to the round-the-clock surveillance. His ongoing spell under house arrest in the Thanh Minh Zen Monastery is just the latest in a long line of incarcerations beginning in 1975, when the communist government consolidated control over South Vietnam, rounded up critics and put them behind bars.

The relationship between communism and religion has always been a hostile one, and no less so in Vietnam, where the government touts the merits of atheism above all other belief systems. It’s had a hard job enforcing this, however – the Pew Forum on Religion and Public Life counts 16 percent of the population as Buddhists, and eight percent as Christians; religions like Hoa Hao and Cao Dai that evolved locally are also popular. Yet believers need a thick skin – in its annual report last year, the US Commission on International Religious Freedom found freedom of belief to be “very poor” in Vietnam, with the government using a “specialized religious police force and vague national security laws” to suppress the ability to worship.

That apparatus of intimidation and surveillance, refined over nearly half a century of communist rule, has kept Thich Quang Do, as well as his colleagues, in a never-ending cycle of detention. The UBCV, formed in 1964, has been consistently critical of the government, and unlike the officially sanctioned Buddhist Sangha of Vietnam, has never been able to exist as an official entity. Other attempts by religious groups to organize beyond the government’s reach have been snuffed out: in January, the leader of the Buddhist Youth Movement, Le Cong Cau, boarded a plane bound for Ho Chi Minh City, where he planned to meet Thich Quang Do, and was detained. He is now under house arrest.

Although considered a dissident, Thich Quang Do is steadfastly apolitical. Yet with the line between politics and religion in an atheistic, authoritarian state forever thin, the government considers him a thorn in the elite’s side. “I must have the right to carry out our religious activities, but here, the Communist Party does not allow us to do as we want. I am not allowed to speak to the Buddhists, to explain Buddhist doctrine. They want to control everything we do, but we refuse.”

Driving around Ho Chi Minh City and its satellite towns, one could be forgiven for thinking that religious freedom is flourishing. In nearby Bien Hoa, a large Christian community makes use of the dozen or so gaudy and cavernous churches that line the main strip, some of which were built after the Communist Party took power. Worshippers breeze around the grounds of the Most Holy Redeemer church in central Ho Chi Minh City, seemingly at ease with the state of affairs in the country. In his office inside the church compound, however, Father Joseph Thoai, a Redemptorist priest, gestures towards the men at the main gate, who also quietly record who enters and leaves.

“No one has ever been able to destroy religion, because wherever man exists, religion exists,” Father Joseph says. Instead, the government seeks to curb its development. ”They are afraid that when a religion becomes a big organization it will have a large impact on people. They have a dictatorial party, and they don’t want any other forces that have the ability to govern people.”

The Redemptorists have had a similarly acrimonious relationship with Hanoi, and for decades have been vocally critical of government-sanctioned confiscation of church-owned land and property. Outside his office, a group of 20 or so people, all victims of land grabs, queue to seek advice on lodging complaints. Reports of police assaults and arbitrary arrests of Redemptorists are common – Father Joseph has been arrested twice recently, in 2011 and 2013, the latter when he attended the trial of blogger Dinh Nhat Huy. His colleague, Father Anthony, has been severely beaten by police in the past.

The government faces an uphill struggle in containing the spread of dissent, whether it be from a religious source or a political one. Freedom of religion is written into Vietnam’s constitution, Father Joseph notes, but that document unraveled long ago. Religious and political leaders are regularly slandered by the government in an effort to discredit them in the eyes of followers: in February, a court in Hanoi upheld the conviction of Le Quoc Quan, an anti-government Catholic blogger and lawyer, on highly spurious charges of tax evasion. Rights groups across the world have called for his release.

But the upsurge in arrests of dissidents over the past few years can be read as a sign that people are growing increasingly outspoken, and utilizing resources like the internet that the government struggles to control. Ten years ago, no one dared speak out, says Thich Quang Do, but that’s beginning to change.

“Time has passed, and people can use TV and know so much about the rest of the world; 20 years ago they only knew about what was happening in Vietnam. They were like birds in a cage,” he says with a smile and air of nonchalance that belies the stoicism that has kept him sane during his 40 years as a prisoner. “The government cannot control all the people easily, although they know that if they use their freedom to express their own ideas regarding politics, economics, religion, and so on, they must accept to go to jail.”

Rather than fearing the punishments the government could mete out to him for talking to visiting journalists, he welcomes the opportunity to speak. “They can put me in prison any time they want. I’m not afraid, so they need not send me to jail. I’m too old – if I die in prison it will not look good to the outside world.”

The government appears now to recognize this. The iconic monk has been nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize on numerous occasions; already feeling the weight of pressure over the spate of jail terms handed to dissidents in the past year’s crackdown, the government would rather a globally recognized figure be given at least the veneer of limited freedom in his temple compound.

Thich Quang Do may well remain in the temple until he, or the government, moves on. He’s just not sure who will go first. “Willy or nilly they must loosen political control – many people now are asking for democracy in Vietnam, and in the end, if the Communist Party wants to exist, it must change. Everything is changing each day – politics especially, always changing. Some day in the future they must accept other views, other parties. I think so, I want so.”